Tulsa Race Massacre

May 31, 1921

A misunderstanding sparks Tulsa's darkest days, The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

Disclaimer: This page contains historical documents, which include imagery and language that may be considered offensive.

Tulsa Race Massacre

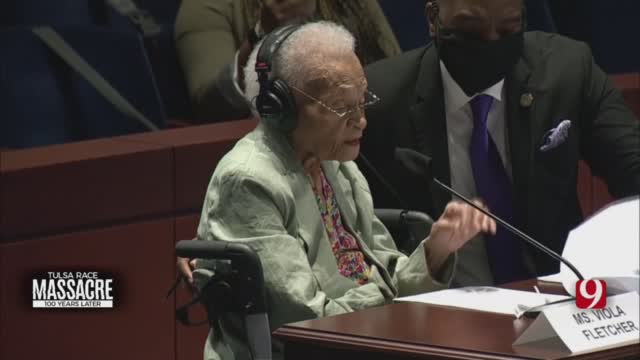

Oklahoma's Own Originals: Tulsa Race Massacre: 100 Years Later

News

News Coverage

Black Wall Street

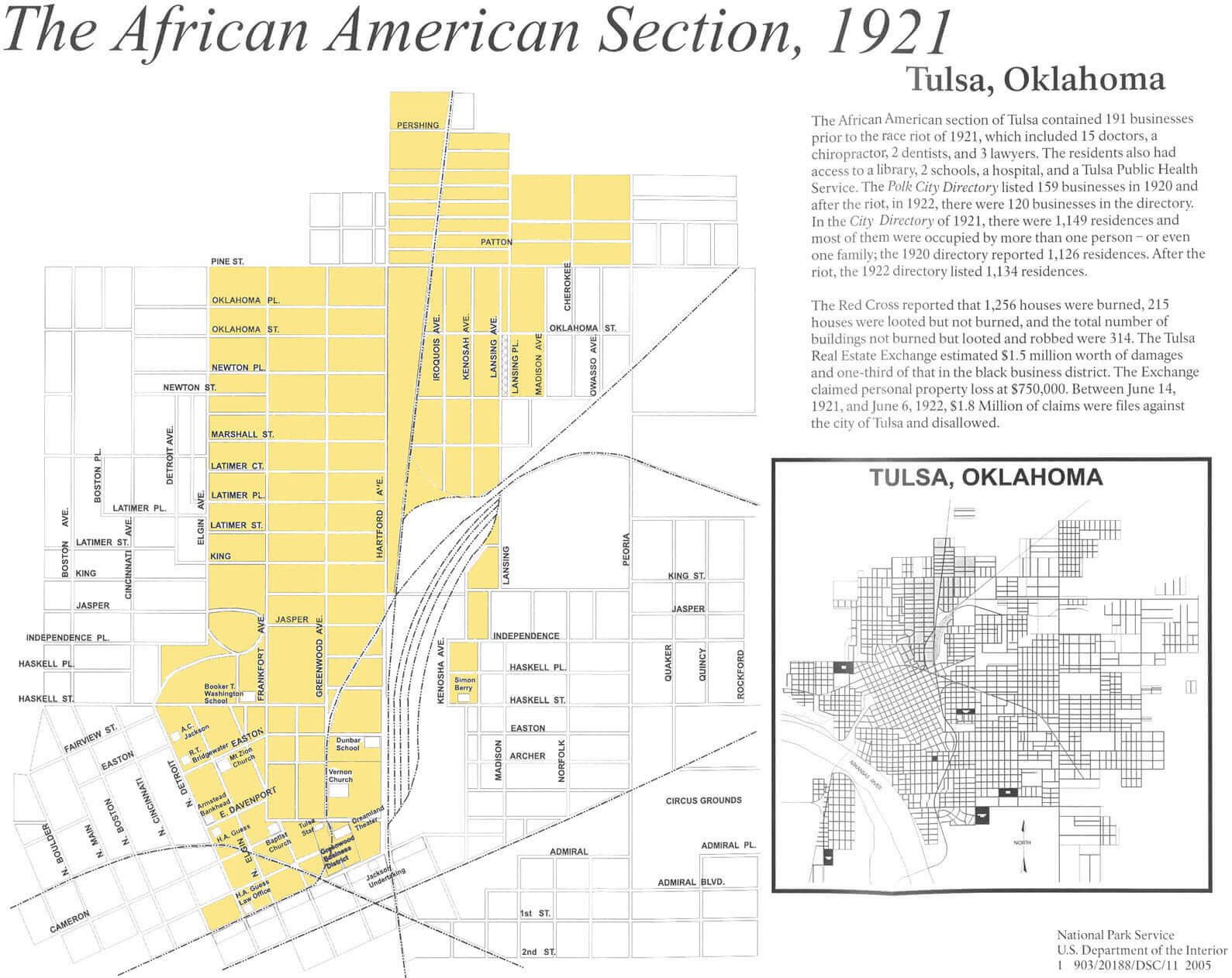

Tulsa in 1921 was a booming oil town with a population more than 100,000. Because of segregation, most of the city's 10,000 African American residents lived in the Greenwood District, a thriving neighborhood of entrepreneurs and families enjoying the American dream.

The area included its own school system, newspapers, a bank, library, and hospitals. It was home to a several churches and 191 businesses, which included shops, a luxury hotel, restaurants, grocery stores, movie theaters, barbershops, salons and nightclubs. The district was also home to 15 doctors, three lawyers and two dentists.

The economic strength and influence of the Greenwood District became known as "Black Wall Street," an area considered one of the most affluent African American communities in the United States.

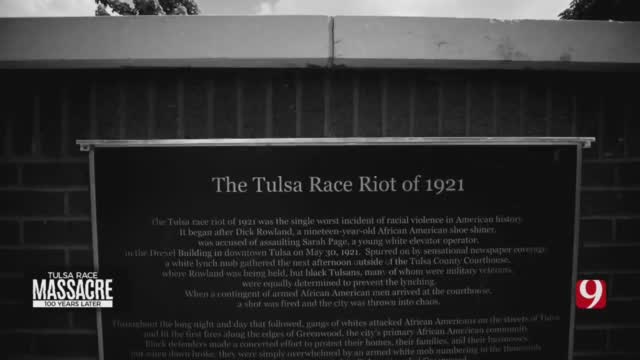

The Accusations

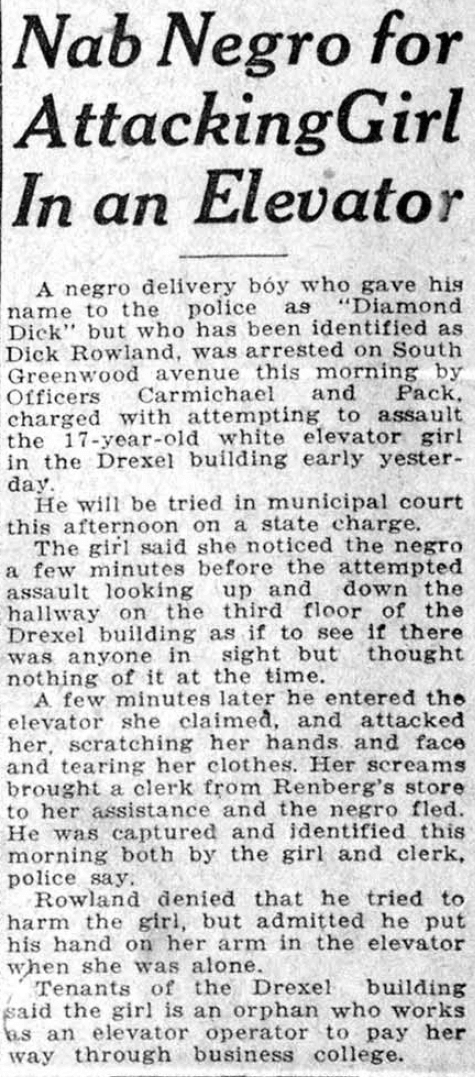

On May 30, 1921, 19-year-old Dick Rowland was shining shoes in front of a downtown Tulsa office building. Due to segregation laws, his only available option for a restroom was on the top floor of the Drexel building. At the time, elevators required attendants, and on this particular day, a 17-year-old woman named Sarah Page was operating the elevator.

When the elevator returned to the first floor, a Renberg's store clerk heard Page scream and saw Rowland run from the building. The clerk reported the incident to police, and the next day Rowland was arrested.

Rowland was accused of sexually assaulting Page, police later determined Rowland accidentally stumbled into the elevator, and to keep himself from falling he had only grabbed the attendant's arm.

News of the accusation spread across the city, setting in motion the destruction of the Greenwood District.

Tensions Increase

The evening of May 31, 1921, hundreds of white men gathered at the County Courthouse where Rowland was being held. A group of these men entered the courthouse to demand Rowland be handed over, the Sheriff refused.

Later, around 9 p.m., an armed group of 25 African American men, most of who were World War I veterans, arrived at the courthouse to help protect Rowland. The Sheriff declined the help and the men returned to the Greenwood District.

The white mob had grown to approximately 2,000 people when a false rumor began to spread around the Greenwood District that the white mens were storming the courthouse. Just after 10 p.m., a group of 75 African American men returned to the courthouse offering help to authorities, but they were again told to leave.

As they walked away, a white man attempted to disarm an African American man, who resisted. During the struggle, a weapon discharged, and both sides began to exchange fire.

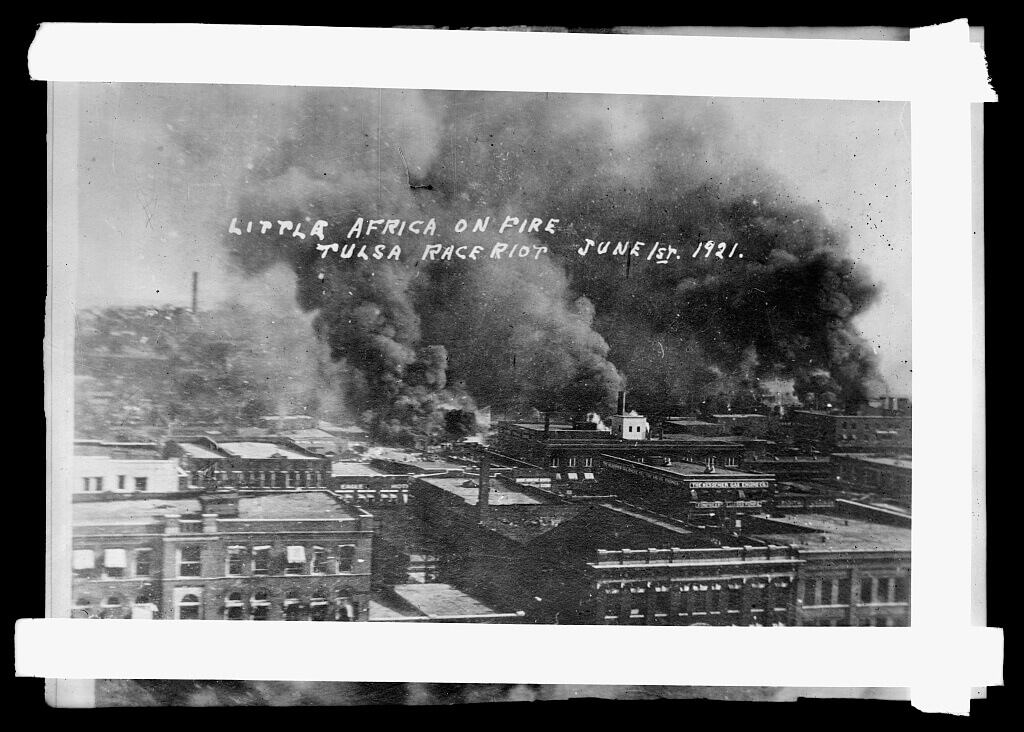

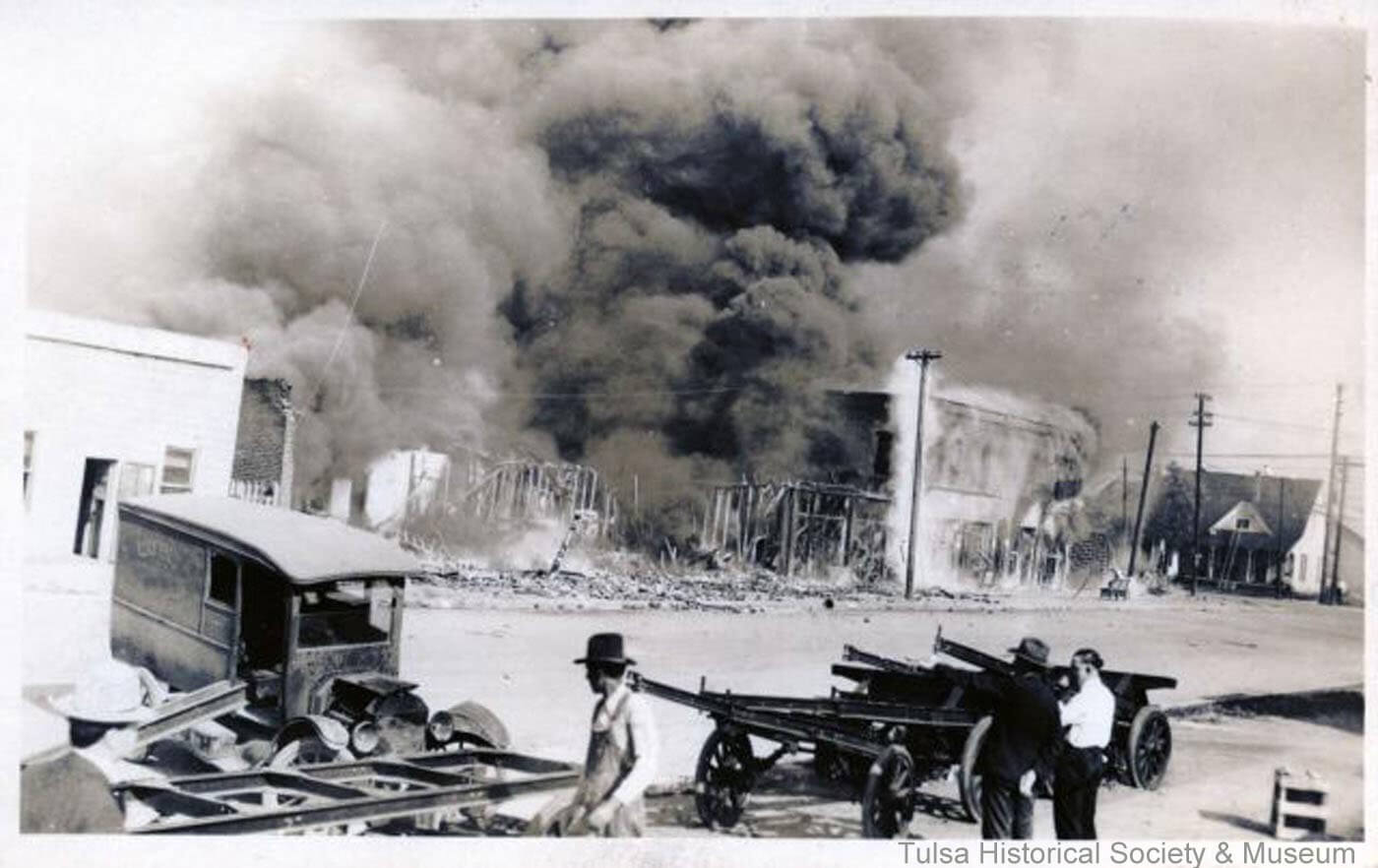

Black Wall Street Burned to Ashes

Over the next six hours, a white mob, some of whom were armed and deputized by the Tulsa Police Chief, began setting fire to homes and businesses in the Greenwood District. While the city burned, white rioters stopped the fire department from entering the neighborhood.

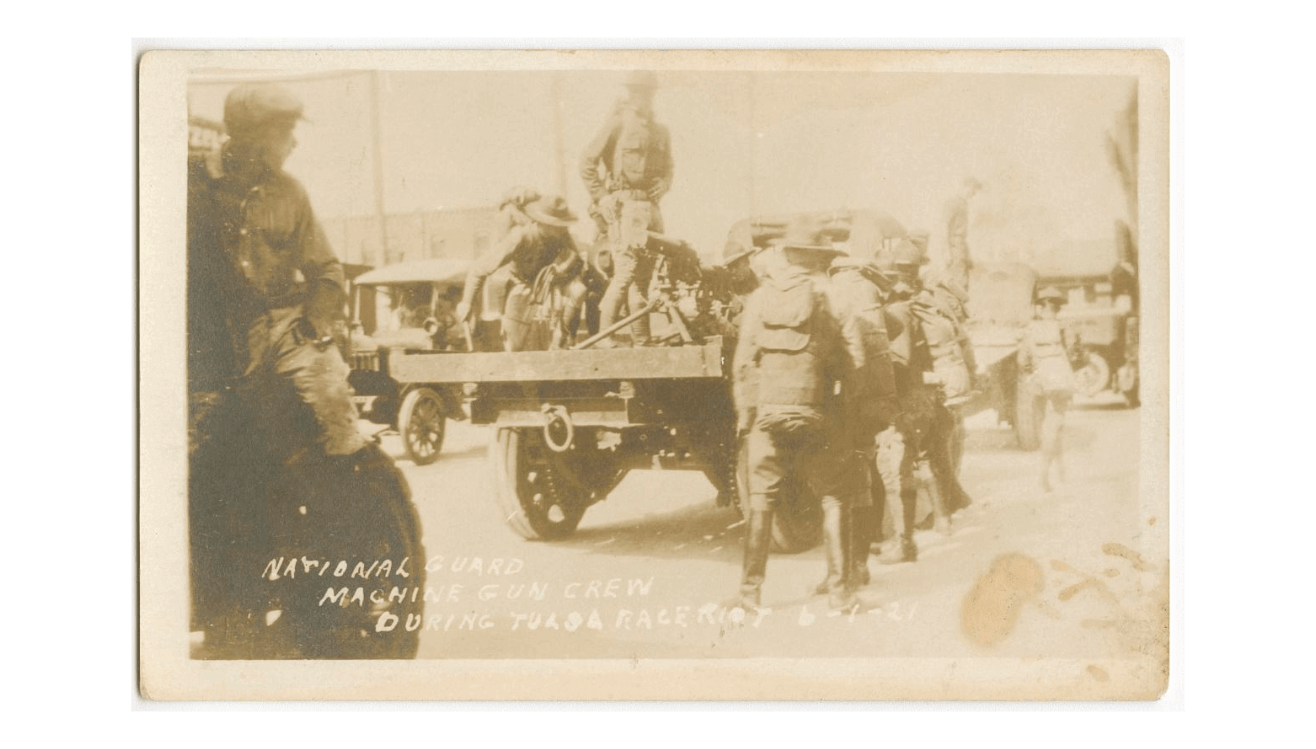

Acts of violence, drive-by shootings, and looting of homes and businesses carried on throughout the night. The lynch mob reportedly killed anyone who resisted, sending others to internment camps. It was reported at least one machine gun was used during the violence, and some survivors claim airplanes were used to firebomb the area.

Black Tulsans fought hard through the night to protect their homes and businesses, but in the end, they were both outnumbered and outgunned.

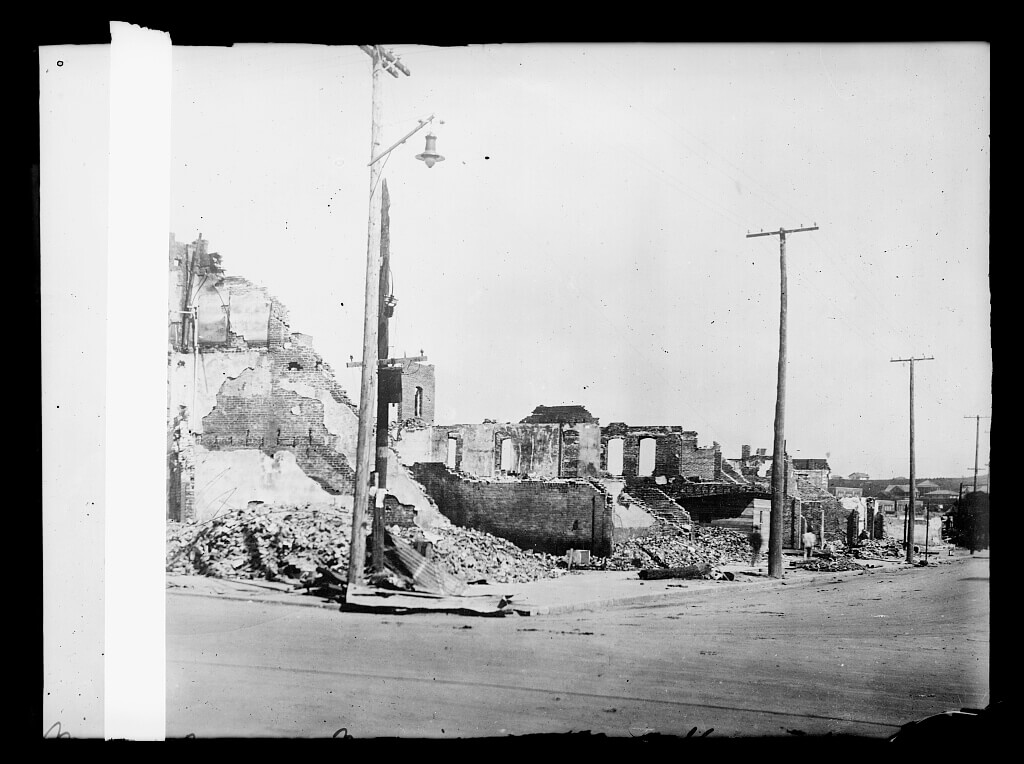

Panoramic image shows destruction of the Greenwood District

Source: Tulsa City-County Library

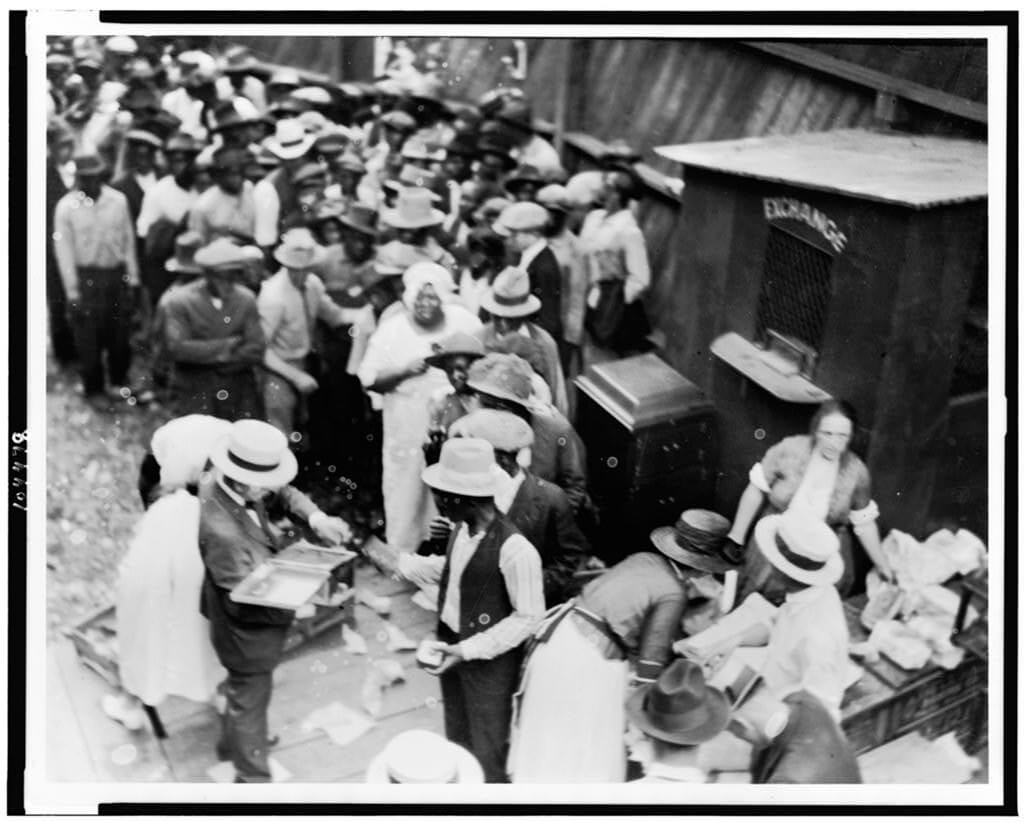

When the National Guard arrived with a declaration of martial law on June 1, the riot had effectively ended. The guardsmen helped extinguish the fires, but they also rounded up nearly 4,000 Black men women and children, taking them - at gunpoint - to makeshift internment camps at the Tulsa Convention Center and the McNulty Baseball Park.

On June 2, nearly 6,000 people were moved to the fairgrounds. Authorities forced these prisoners to clean up the destruction caused by the white mob in their community. The mayor threatened survivors with arrest if they refused to work.

The Aftermath

The Greenwood Cultural Center estimates that hundreds were killed, 35 city blocks were reduced to ashes, 1,256 homes were destroyed, with another 400 looted leaving thousands more without shelter and livelihoods.

Historians believe the death toll of the Massacre could be as high as 300. However, the Oklahoma Bureau of Vital Statistics officially recorded 36 dead: 26 Black and 10 white.

"There's really no way of knowing exactly how many people died. We know that there were several thousand unaccounted for," Mechelle Brown, program coordinator for the Greenwood Cultural Center, said during a 2016 interview.

Within days of losing nearly everything, and with no help from the city, Black Tulsans were already beginning to rebuild with help and donations from the Greenwood Community, Black churches, the NAACP, and other Black townships in Oklahoma.

Charges against Dick Rowland were dropped following the Massacre. However, an all-white grand jury blamed Black Tulsans for the destruction of the Greenwood District. No whites were ever prosecuted or punished for their rioting.

Rowland reportedly left Tulsa and never returned.

Historic News Coverage

Disclaimer: This page contains historical documents, which include imagery and language that may be considered offensive.

June 2, 1921

- The Morning Tulsa Daily World, Final Edition

- The Daily Ardmoreite, Home Edition

- The Morning Tulsa Daily World, Final Edition

- New York Tribune | New York, N.Y.

- The New York Herald | New York, N.Y.

- Evening Star | Washington, D.C.

- The Evening World | New York, N.Y.

- The Washington Herald | Washington, D.C.

- Evening Star | Washington, D.C.

June 3, 1921

- The Chickasha Daily Express

- The Daily Ardmoreite

- The Morning Tulsa Daily World, Final Edition

- The Guthrie Daily Leader

- The Chickasha Daily Express

- Durant Weekly News

- The Topeka State Journal

- New-York Tribune | New York, N.Y.

- The Washington Times | Washington D.C.

- The New York Herald | New York, N.Y.

- Evening Star | Washington, D.C.

June 10, 1921

June 14, 1921

June 20, 1921

June 21, 1921

June 23, 1921

June 23, 1921

July 4, 1921

July 11, 1921

July 14, 1921

July 15, 1921

July 16, 1921

July 18, 1921

July 19, 1921

July 20, 1921

July 23, 1921

July 27, 1921

July 29, 1921

June 18, 1921

August 7, 1921

August 8, 1921

August 13, 1921

August 15, 1921

August 17, 1921

August 17, 1921

September 30, 1921

October 14, 1921

Additional Resources

For additional historic coverage and information please visit the following sources.

- The Attack on Greenwood

- Black Wall Street: Then and Now

- The Tulsa Race Massacre | Oklahoma History Center Education Department

- Tulsa Race Massacre | Oklahoma Historical Society

- A Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921

- The 1921 Tulsa Massacre: What Happened to Black Wall Street

- Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 | OSU Digital Collections

- 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre | Tulsa City-County Library

- Photo Album of the Tulsa Massacre and Aftermath

- Tulsa Race Massacre Photos

- Affidavit's, Telegrams and Other Documents

- Spirit of Greenwood: Prosperity & Perseverance

- Remembering the Race Riot

- Documents & Court Cases

- Tulsa's 'Black Wall Street' Flourished as a Self-Contained Hub in Early 1900s

- Tulsa Race Massacre

- 1931: The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims

- Tulsa to Search for Mass Graves From the Race Massacre of 1921

- Black Wall Street on film: A story of revival and renewal

- Final 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey

- Tulsa-Greenwood Race Riot Claims Accountability Act of 2007

- Greenwood and the Tulsa Race Riots

- Tulsa race massacre of 1921: The painful past of 'Black Wall Street'

- How the Tulsa Race Massacre Was Covered Up

- What to Know About the Tulsa Greenwood Massacre

- The Tulsa Massacre and the Destruction of Black Wall Street | The Case for Reparations and H.R. 40