Rural Oklahoma Faces Critical Doctor Shortage

<p>Two Oklahoma counties - Grant and Greer - have zero primary care physicians. Another eight counties have just one, and 29 others have fewer than 10 doctors.</p>Thursday, September 7th 2017, 6:42 pm

One of the biggest challenges facing state leaders, when it comes to health care, is trying to make sure that all Oklahomans, especially in small towns like this, have access to good medical care.

A good indicator of the magnitude of this challenge is the fact that 75 of the 77 counties in Oklahoma are considered Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSA).

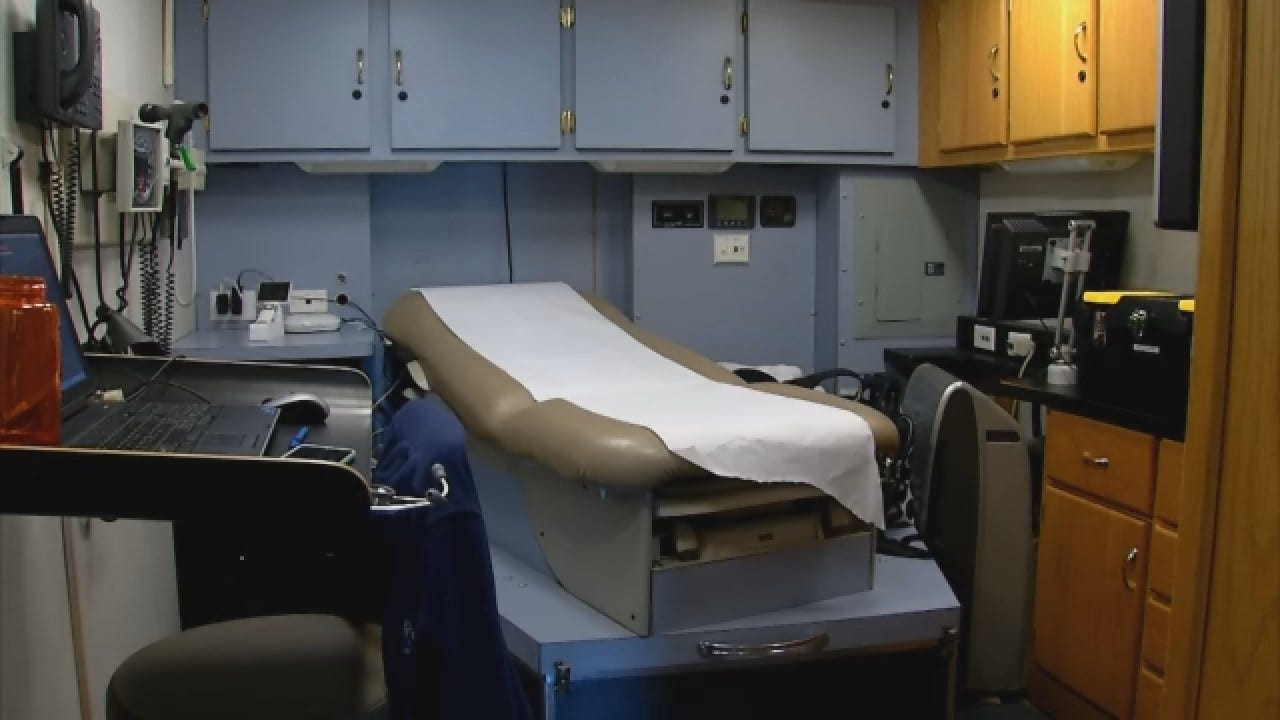

Another indicator is what we observed on a recent visit to the medical clinic in the heart of Beaver County.

"How long has this been going on?" asked Dr. Gary Mathews, in one of the clinic's exam rooms,

"Oh, probably four or five days," answered Ginger Dailing, who lives in Beaver.

Dailing is grateful for the medical care she gets at her hometown doctor's office.

"We have amazing nurse practitioners here," Dailing was quick to point out, "we have had some young doctors, but they don't stay too long."

Currently in Beaver -- in all of Beaver County -- there is one practicing physician.

"Yes, that's me," said Dr. Mathews, allowing a wry smile to crease a face that has weathered more than 73 years, much of that time in the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles.

Dr. Mathews came to Beaver seven years ago; he needed a job and Beaver needed a doctor.

"There's been a rapid turnover of doctors here," Mathews stated.

Mathews seems content to stay, but given his age, it's unclear how much longer he'll be able to practice. Age aside, he's still just one doctor, working with three nurse practitioners, having to handle everything from ingrown toenails to major trauma.

"The emergency room puts a little pressure on all of us because we see all kinds of cases," said Dr. Mathews, "not a lot of them, but some very serious cases that none of us were really trained to handle."

The ER is at the small hospital across the street from the Community Clinic of Beaver. The hospital has about a dozen beds and offers telemedicine, which gives patients access to specialists in Oklahoma City. Still, telemedicine has its limits -- any sort of surgery means the patient will have to be transported.

"You have someone that comes in that is having a stroke," explained Susan Trippet, one of the three nurse practitioners -- "Yes, we're able to give them the medicine and ship them on to a stroke center, if the weather permits."

Just days before our visit, Trippet said, they needed to fly someone out, but couldn't.

"The cloud cover was too bad," said Trippet, "and that's frustrating thing part of it."

Fortunately the sun was shining last year when Don Brown showed up at the emergency room with chest pains.

"Within probably three hours," Brown said, "they airlifted me out of here to Oklahoma City."

Brown grew up in Beaver, moved away, but then moved back in 1980. He says he's seen the town go from having four doctors then to one now.

"We need doctors in rural Oklahoma for old people like me," pleaded Brown.

Beaver County is not alone in having just a single practicing physician and, in fact, in some counties there aren't any.

According to the 2017 County Health Rankings, two Oklahoma counties -- Grant and Greer -- have zero primary care physicians. Another eight counties, including Beaver, have just one; 29 other counties have fewer than ten doctors.

The problem is not entirely new. More than 40 years ago, stat lawmakers created the Physician Manpower Training Commission (PMTC) to "enhance medical care in rural and underserved areas of the state."

Dr. Jack Beller serves on the PMTC and says their mission is more important then ever, because the problem has become worse.

"It's estimated that about 40 percent of the people who live in those underserved areas are not getting their proper medical care," Beller explained during a recent interview.

It doesn't matters that many rural hospitals are struggling to keep their doors open. 94 of Oklahoma's 157 hospitals are considered rural, and as of last year, experts estimated 42 were at risk of closing.

"And it doesn't take, ya know, but one more provider cut, or the loss of a physician in the community," said Andy Fosmire, with the Oklahoma Hospital Association, "for [a hospital] to go from being on solid ground to being off the cliff."

State leaders are well aware of these problems, but have been largely unable to make any progress recently through legislative efforts.

Of five bills introduced during the 2017 regular session, legislators passed just one, a bill requiring that state-funded medical schools give Oklahoma students priority consideration when assigning clinical rotations -- hardly a game-changer.

"There are certain advantages to living here," Dr. Mathews pointed out, as we wrapped up our interview.

Mathews hopes more young physicians will see the upside to doctoring in a small community, as he did. Although, he admits, it took him a while to see the light.

"I really thought I was going to go into research," Mathews said, "it just didn't turn out that way."

More Like This

September 7th, 2017

April 8th, 2025

April 7th, 2025

Top Headlines

April 16th, 2025

April 16th, 2025