Deep Roots Of Deep Deuce: Former Residents Remember Neighborhood They Were Forced To Leave

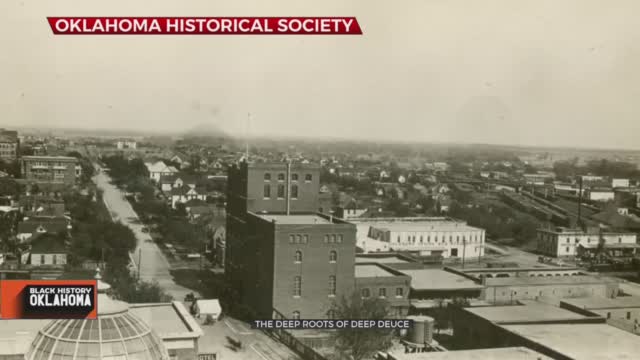

The Deep Deuce District on the edge of Bricktown is filled with trendy restaurants, apartments, and high-end brownstones, but it was once an instrumental part of Oklahoma City's Black History.Wednesday, February 23rd 2022, 9:47 pm

OKLAHOMA CITY -

The Deep Deuce District on the edge of Bricktown is filled with trendy restaurants, apartments, and high-end brownstones, but it was once an instrumental part of Oklahoma City's Black History.

"I never knew that I was walking in history or around history," Anita Arnold, Black Liberated Arts Center executive director said.

In the 1920's Deep Deuce was a thriving Black community.

"It was exciting. It was amazing. It was culturally enriching. It was a lot of things to a lot of people,” Arnold said.

During the day Black-owned medical offices, theatres, and other businesses bustled with customers.

At night, the soulful sounds of blues and jazz filled the streets, greats like Charlie Christian, Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday all played and stayed here.

“They were only allowed to stay in these Black-owned hotels, eat at those restaurants, so that's what this area held for us so it was a safe zone for people that were traveling through,” Bob Davis, former preacher at Calvary Baptist Church said.

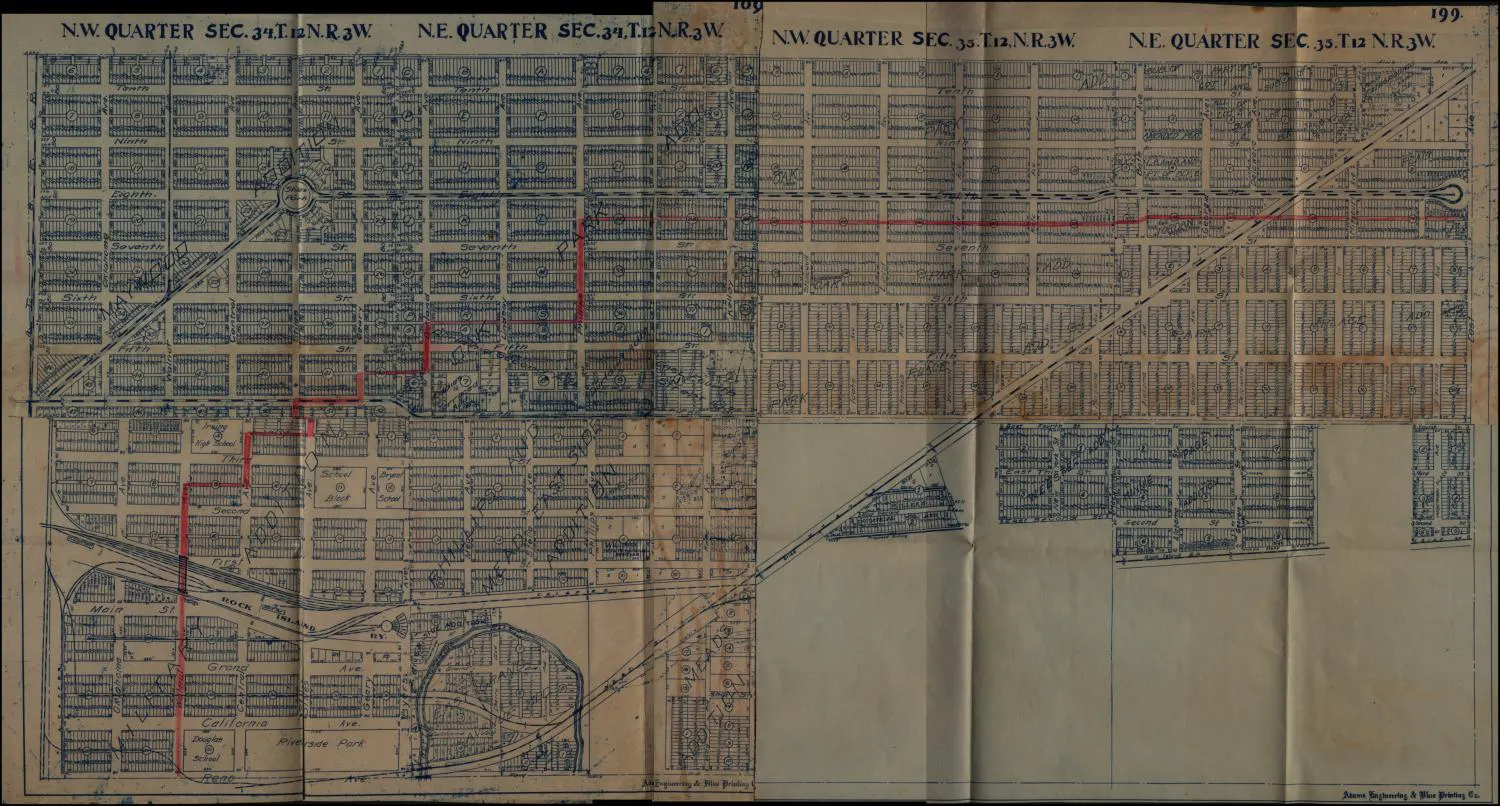

The safe space rose out of the Jim Crow era. An Oklahoma City map from 1933 displays the segregated areas in Oklahoma City. The red line shows the division mandated by City ordinance between Black and White neighborhoods.

City mandates were put in place to assure this. An emergency ordinance from 1918 ordered separate blocks for residences by “white and colored people.”

The document states. "it shall be unlawful for a White person to use a residence, or place of abode, any house, building, or structure, or any part thereof located in any colored block, as the same in hereinafter defined, and it should also be unlawful for any colored person to use a residence or place of abode, any house, building or structure, or any part thereof located in any white block as the same is hereinafter defined.”

"It was an economy, Second Street. It was African Americans supported each other and they created their own economy," Arnold said.

Businesses ranged from anything you can think of clothing stores, barber shops, a black owned newspaper.

"I was working at Randolph Drug Store behind the soda fountain behind the soda counter and I made malts and sundaes and stuff like that, and Dr. Randolph was a pharmacist,” Arnold said.

Dr. Randolph also served as the first Black principal of Oklahoma City's school for Black students.

Homeowners in the area became leaders in the community fighting against racial injustice. Many of the meetings for the for the cause were held at the Calvary Baptist Church.

“They use to call it a silk stocking church back in the day and that phrase just kind of meant it was the place to be. It would be full as has been told to me. It would be full on the Sunday mornings. You had to get in early to make sure you had a seat,” Davis said.

"Martin Luther King Jr. graduated from seminary at an early age. He stood right here in this pulpit and preached a sermon,” Davis said.

Bob Davis was the former preacher.

“Strategies for a number of things that happened during the Civil Rights movement, Clara Luper and others who were part of that. They came to this spot to repair those students who did sit ins downtown and various places," Davis said.

But over time the buzz around Deep Deuce began to fizzle out and developers noticed.

"So I think you have to go back to the beginning of Urban Renewal. It was originally created to help redevelop blighted areas and the first area of focus was downtown,” Cathy O’Connor, president for the alliance of economic development said.

In the 70s, Urban Renewal began working with the Oklahoma Department of Transportation for the construction of I-235 which would go right through NE 2nd.

"Urban Renewal was also known as urban removal. It was about removing as they say for the public good," Gary Royal, former president of the Harrison-Walnut neighborhood association said.

Gary Royal was the neighborhood president back then. Residents and Civil rights leaders tried to stop the project, but after years of fighting in the mid-1980's Construction of I-235 began.

"Hundreds were impacted directly and indirectly. As a community we were impacted. We lost. It's in here, it's in your heart. It's in your soul. It can't be replaced, so there's still a sense of lost,” Royal said.

Families were moved to the J.F.K neighborhood and many businesses were either demolished or forced to close.

“I don't think they completely understood the impact in neighborhoods that had or that it had at the time and continues to have. It disrupted places where people grew up where their grandparents lived, where they went to church all of those things and I think that had a really detrimental effect particularly the Black community in Oklahoma City,” O’Connor said.

According to the 2020 U.S. Census, the once thriving Black community is now home to about 1,000 white people and nearly 90 Black people.

When you walk through the area, residents said there's barely anything left that resembles the Deep Deuce they loved. Upscale apartments now line the streets of the neighborhood and what wasn't demolished has been turned into places like restaurants and hotels.

“Folk that occupy the spaces down there now. They don't even really know the history. They make up stuff I think at times you know that's not true,” Arnold said.

“And unfortunately, that is the past that we inherit here at urban renewal but we do work very hard today to try and create some type of reconciliation and repair some of that damage that was done in the past," O’Connor said.

“It's just you shouldn't have to tear everything down and move everything out to show some progress. It looks good, but the families that use to live here are not here though. It's okay though we move forward. It's life,” Royal said.

More Like This

February 23rd, 2022

February 22nd, 2023

February 15th, 2023

Top Headlines

December 21st, 2024

December 21st, 2024

December 21st, 2024

December 21st, 2024