Reign Of Terror: The FBI Investigation

Osage murders in the 1920's known as the Reign of Terror, were investigated by the FBI. News 9's Washington Bureau Chief Alex Cameron sat down with the FBI's historian.Wednesday, October 18th 2023, 10:11 pm

WASHINGTON, D.C -

The Killers of the Flower Moon book and film are based on the true events of the murders of several Osage Nation members in the 1920s. It is known as the “Reign of Terror,” when the Osage were killed for their land and oil money. More than 200 tribal members were killed during that time, but only about 30 murders were solved.

”The way the case had been going before the bureau started to get involved... I don’t think the cases would’ve been solved at all,” FBI Historian John Fox said. As a historian, and specifically the FBI's historian, Fox makes that statement, based not on feel but fact; and notably the fact that, unlike others who'd been brought in to solve the murders, the FBI agents, he said, were above corruption and produced convictions. They certainly made use, as best they could, of the tools that were available,” Fox said. “But this was a time when forensic science was in its infancy.” Just as the FBI was.

Far from being the storied agency depicted in the FBI's in-house museum in Washington, D.C. The agency that would catch the Unabomber, the BTK killer and catch the imagination of the American public by taking down gangsters like John Dillinger. The FBI was more or less unknown in the early 1920s when the Osage murders were taking place. “The bureau of investigation, as the FBI was called, was pretty small,” Fox said. But a man named J. Edgar Hoover took the reins in 1924, as Osage leaders were pleading with the Bureau of Indian Affairs for help. “They turned to the bureau of investigation, and it was Hoover who basically sent out the memos from Washington to our office in Oklahoma City, saying, 'Get on this,’” Fox said. Fox said the first agents to work the case developed strong suspicions around Bill Hale, a powerful cattleman, and the uncle of Ernest Burkhart.

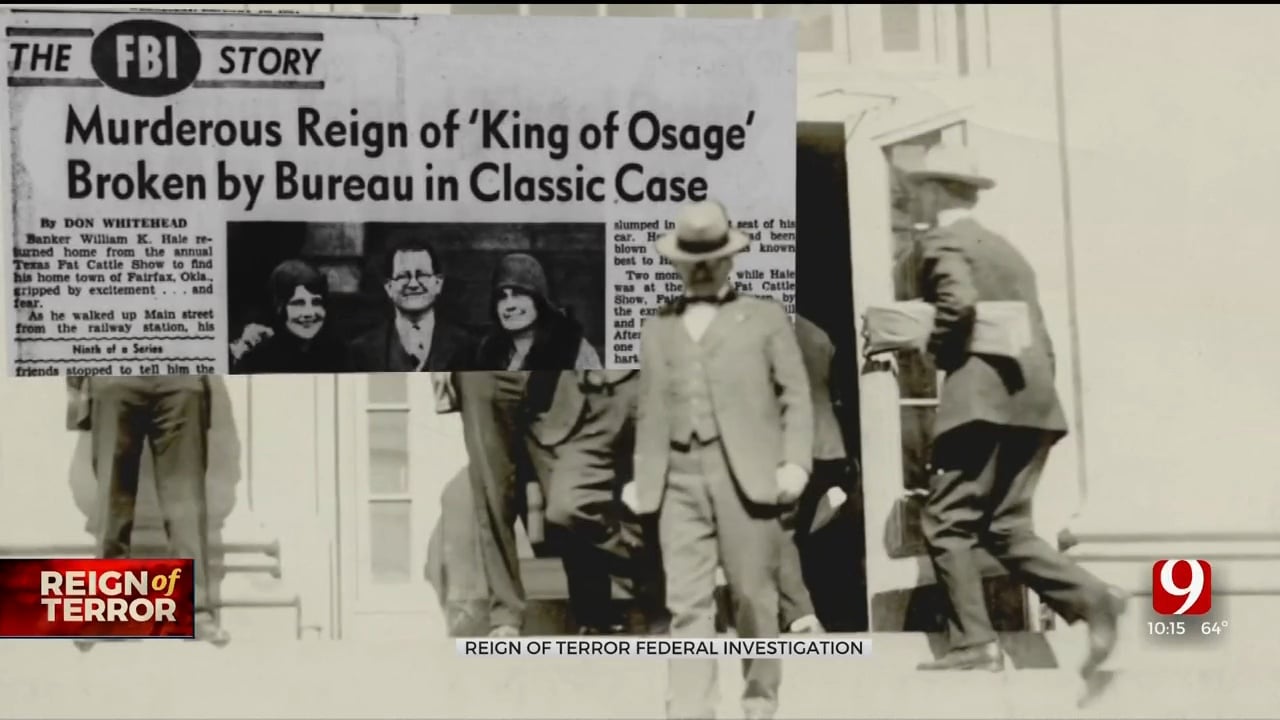

The self-proclaimed “King of the Osage Hills,” Hale owned a controlling interest in a local bank and held considerable political influence, one reason those agents hit a dead end. “People weren’t willing to speak. People were fearful, and, of course, the Indians themselves didn’t always trust the latest person to come knocking on the door, wanting to know more,” Fox said.

Under pressure to show that his agency was not only above board, but competent, Hoover made what turned out to be a critical decision. The bureau realized it had to try and do something different, and that’s when Hoover, among other things, assigned Tom White as the head of the Oklahoma City office. A former Texas Ranger and railroad security man, White took charge of the investigation in 1925, and Fox said it was under White that agents tried something that had not been done much before -- they went undercover. “By basically integrating themselves into the economy and the society there, they were able then to build trust with people...and in doing so, of course, are able to gather the evidence that really allows them to focus on Hale,” Fox said. The FBI saw Hale as a kingpin.

Investigators focused on murders that, in addition to being committed on tribal land where they had jurisdiction, also seemed to have a clear link to Hale, like the execution-style shooting of Henry Roan. “It was clear that Hale was involved in something. Ya know, right after Roan was found murdered, Hale came out and tried to make a claim on the insurance policy that he’d taken out on Henry Roan,” Fox said. They looked into the shooting death of Anna Brown and the house explosion that killed Rita and Bill Smith -- all of them related, all pointing to someone trying to amass a fortune in headrights. “And so the bureau’s agents were able to identify a couple of witnesses who had worked on aspects of the various plots that Hale had going, and eventually get them to testify before the grand jury so that indictments could be put forward,” Fox said.

Ernest Burkhart was one of those to testify, turning on his uncle in 1926 and pleading guilty to being part of the conspiracy. Hale had persuaded Burkhart to marry Mollie Kyle while simultaneously arranging for the murders of her family: Anna Brown, Henry Roan, Rita and Bill Smith. And investigators believed Mollie was being slowly poisoned, too. Despite hung juries, appeals and every attempt to manipulate the system, Hale was convicted in 1929 and, like Burkhart, was sentenced to life in prison. Both were later paroled, with Hale becoming a free man in 1947. “He was forbidden from going back to the Osage territory,” Fox said. “He ended up in, I believe, Phoenix, waiting tables towards the end of his life.”

Hale died in 1962 at age 87, a long life compared to those he cut short, in a brazen attempt to take wealth that wasn't his. “He was definitely a cold-blooded criminal,” Fox said. “How does he rank in the bureau's pantheon of villains? He’s certainly up there.”

Fox helped David Grann with Killers of the Flower Moon, but admits he is not a big fan of its subtitle, saying he does not see the Osage murder case as the birth of the FBI. Still, he appreciates that the book and movie will give people a better understanding of what the FBI does, which in 1920s Oklahoma, he said, was very good work.

More Like This

October 18th, 2023

February 6th, 2025

January 30th, 2025

January 23rd, 2025

Top Headlines

April 16th, 2025

April 16th, 2025